Chapter 7: Early Christian Church and Education

|

Chapter 7: Early Christian Church and Education |

The practice of making and inscribing leavened bread continued during the early Christian era. Galavaris[1], in Bread and the Liturgy, describes the development of breads used by Eastern Christians both in religious rites and at home. His sources of evidence are bread stamps and bread molds. Bread and cake molds had concave designs at the bottoms which would form a relief figure on the top of the baked goods when they were turned out of the mold. Such a mold was found in Athens several years ago with a decoration that is the facade of a temple. It is thought to be the oldest mold for cake in existence. The bread stamp was another way of impressing a design upon a loaf of bread and needed to be done before the bread began to rise.

From the first to the fourth centuries, Christians made use of extant designs for their bread which could be understood by other Christians to have religious significance but which were borrowed from pre Christian, pagan, sources and thereby served as a disguise since, to be identified as a Christian could lead to persecution. For example, the panis quadratus, a round loaf of bread scored into equal quarters by intersecting lines served the general Roman household, the deep lines acting as guides for easy fraction of the loaf. Christians surreptitiously used this loaf for their oblations, the intersecting lines of the loaf which divided it into four sections also served as a designation for the sign of the cross, and by slightly altering the angle of intersection of the lines, Galavaris tells us. The Greek letter X was the result, the letter standing for Christ.

Here is evidence, then, that the early Christians were using bread as escagraphs almost in the Trademark/Name league (for, after all, the bread could be identified as having been made by another Christian, thus, trademarked) or it could be seen to have the Bread-of-Bernice informational stricture that marked it for a specific ritual only. Galavaris[1] also mentions the use by Christians of another commonly available bread called the panis trifundus, its three divisions used by Christians as a symbol for the Holy Trinity.

It is compelling to observe that early Christians made use of a standard bread form which they physically altered slightly and another to which they adjusted the traditional meaning in order to have a way of signaling other Christians who they were and also to use for their personal religious practice. If we are convinced by Galavaris, who tells us that the Christians "faked" one kind of bread (panis quadratus) and altered their way of thinking about another (panis trifundus) then we are faced with extraordinary evidence that early Christians knew how to play the escagraph game.

Sometime in the fifth or sixth centuries, when it became less than lethal to reveal one's belief in Christ, Christian bread stamps with inscriptions came into existence. Galavaris describes one found in Christian Egypt which carries the inscription "Light and Life" in Greek and another with the Greek letters Kappa and Chi which Galavaris reckons, might stand for the Lord Christ. Even though identifiably Christian, these stamps are still reasonably reticent about Christian declaration.

Less equivocal inscriptions appeared in the middle to late 6th century, writes Galavaris, a good example being that of a stamp now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna which has a contested inscription, for which the possible readings are: "I seal with the Holy God," "I seal in the name of the Holy God," or "I seal the Holy God." The uncertainty arises over incorrect usage which, Galavaris says, is typical of Christian bread stamps. If the latter reading is correct, then Galavaris believes that the stamp is sealing the Holy God, the bread that is understood to be the body of Christ, and therefore, represents one of the early stamps used to segregate Eucharist bread from the several other varieties of bread that could be and often were stamped and used by Christians, making them Informational escagraphs.

Today, the Eastern church still uses leavened bread for the Eucharist and it is still marked to segregate it from the bread meant for daily consumption. The western Church uses unleavened bread and no requirements that it be marked are set down. Of interest is a decree argued to have been made by Edward VI of England (reigned 1547-1553 - only legitimate son of Henry VIII) which John Ashton[2] brings to our attention in The History of Bread. The decree says that wafers for the Eucharist of the Church of England be "...without all manner of print..." and little reason is given for this decree except that Ashton claims Edward VI was a religious zealot and some idea of purity was felt to be protected by his order. Edward VI was intensely devoted to Protestantism. Other reasons for this decree may have come from the ruthless regents (Somerset and later Northumberland) who ruled behind the mask of Edward VI.

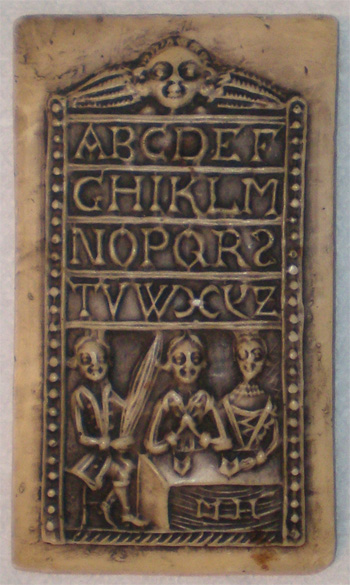

Early in my search for the history of the escagraph, I discovered Marrou's [3] A History of Education in Antiquity, in which he describes the sometimes brutal teaching methods of first century Romans and the doubts they finally had about the effectiveness of those methods. They began, instead, he says, to use competition and prizes in order to encourage students rather than the beatings they had earlier prescribed. They offered students wooden or ivory letters to play with in order to learn the alphabet. Marrou goes on to say: ". . and, when they first began to get things right, rewarded them with little cakes, especially cakes in the form of the letters that they were trying to learn" (emphasis mine).

None of the citations he gives for that entry say any such thing, not Gaidoz[4], not Horace, not St. Jerome nor Quintilian say anything like cakes in the form of the letters were used as an incentive to learn. The closest any author comes to Marrou's claim is Gaidoz who mentions the cake upon which the alphabet had been written for the young student Columba and, as we have seen, that was a cake upon which the alphabet was written and was not individual alphabet cakes. None of those authors mentions cakes in the shape of alphabet letters; but, they do mention alphabet letters made of wood or ivory. It's a safe assumption that children were awarded with cake or biscuits to encourage them to learn the ABC's, but cakes in the shape of the alphabet doesn't seem to match the evidence.

The name of the Gaidoz essay in Vieweg's[4] Melanges Renier collection is "Gateaus Alphabetiques," and is clearly in the plural but, Gaidoz' critique of the legend from the Leabhar Breac[5] is clearly about one cake with one whole alphabet written on it. Gaidoz offers interpretations of why eating an alphabet cake might cause a child to instantly know the alphabet. He mentions the superstitious belief that mixing written messages into prescription drinks and salves and then swallowing them or applying them can cause healing but settles, instead, for the simpler reasoning that the cake with an alphabet on it acts as an encouragement to the student and declares that to be the most reasonable explanation of why such a method was believed to work.

Gaidoz rhetorically asks whether it could have been possible for the Irish to have invented this attractive way of teaching. He thinks not. In fact he writes with some pronounced prejudice that "...the Irish have less right than any other people to certificates of invention in matters of civilization." His claim is that it was Christian Romans and Germans who brought this practice to the Irish who copied it and carried the tradition forward. He offers nothing else than his clear prejudice against anything Irish (he calls them mastodons) as a source for the belief that Romans and Germans brought alphabetic cake to Ireland. Unfortunately for Gaidoz, and for Marrou[3] who misinterpreted his work, there is no evidence that Romans practiced any such pedagogy as alphabet shaped cakes and as for it being a German practice, Gaidoz offers no source as evidence.

It is my belief that, not until some time after the introduction of

movable type in Europe and England, is there any evidence of single

alphabet letters made on any scale of an edible substance in either Europe

or England. I

found the first evidence of a single, edible alphabet letter in an

English cookbook called A Daily Exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen

by John Murrel[6]. The Egyptian phonemes /t/ and /n/ were the first examples of a single,

edible, writing character to have existed and they were created only because

bread and water happened to be pronounced with the initial /t/ and /n/ and

not because the populous was beginning to grasp the concept of single,

individual letters.

The MacEgans, an Irish clan, claim that one of its ancestors wrote the manuscripts included in the Leabhar Brecc in which the Columba legend first appears. Whoever wrote the legend either invented the idea of the alphabet on a cake, borrowed the idea or fused a new one from practices already extant. The cake in the Columba legend seems to be a complete alphabet on a flat surface which corresponds nicely with printing practices before the invention of movable type, that is, page plates carved into a block of wood where a complete page of a manuscript makes up one plate. Also, keep in mind that the Columba legend was compiled and included in the Leabhar Brecc in about the year 1411, 39 years before 1450, the date of the establishment of the movable type press. That means that the legend was written sometime in the late 14th century or the early 15th. Columba's cake looked like a complete printed page or the wood block positive of a carved negative page, a block print.

We turn to the educational practices of the Jews as reported in a work by Hayyim Schauss[7] , Lifetime of a Jew, who tells us that, in the first centuries of Palestine, the Jews organized beis ha-sefer (house of the book), establishments usually attached to a synagogue which were rudimentary schoolrooms where boys of five to six went to learn to read, write and learn the Torah. The teacher would write the Hebrew Alphabet on a slate, along with some verses from the Torah, and then read them to the child who would repeat them. Next, the teacher spread some honey on the slate and bade the boy lick off the alphabet and verses. That practice was based on Ezekiel 3:1-3 which states:

Moreover he said unto me, Son of man, eat that thou findest; eat this roll, and go speak unto the house of Israel. So I opened my mouth, and he caused me to eat that roll. And he said unto me, Son of man, cause thy belly to eat, and fill thy bowels with this roll that I give thee. Then did I eat it; and it was in my mouth as honey for sweetness.

Schauss goes on to say that the boy learning his alphabet was also given a honey cake with inscriptions on it, fruit and a hard cooked egg with verses inscribed on its shell. The inscriptions on the cake and eggs were read to the child and he repeated them. "The lesson was now finished," says Schauss, "and the child was given the cake, the egg and the fruit to eat." The egg was not escagraphic because the writing on the shell is not eaten, keeping in mind the Sunkist example. I draw attention to the slate smeared with honey because it is the oldest and clearest example of the combination of sweetness and alphabet letters I have encountered, as Schauss has pointed out, in the first centuries at Palestine.

The sweet alphabet on a slate is not all that different from the alphabet on a cake that Columba was given. Perhaps the author of the Lebhar Brecc, had encountered such a teaching method in reality, story or legend. It should compel our notice that the two types of learning:

both involve boys who are beginning the process of learning the alphabet for reading, and especially for reading religious documents.

The MacEgan who purportedly composed the legend may well have altered the conditions, from the Jewish source where he could have heard it, to suit Irish expectations. Whatever the case, here are two educational practices involving sweet escagraphs and alphabet learning. They should hold our attention for long enough to note that both are combinations of the powerful and magical tool for reading and writing which the student was embarking on learning, the alphabet, coupled with sweetness, a powerful commodity. Sugar, as the sources we have looked at confirm, had begun to be available to the lower ranks of aristocracy and administration by the 15th century so sugar would be a commodity which, at least, the writer/compiler of the Lebhar Brecc had encountered. But. in all likelihood, the cake Columba ate was made with a sugar substitute, honey, since Columba lived 6 centuries prior to sugar's introduction into England. Certainly, the Jewish pedagogical example we examined occurred before sugar made its way out of the East and prescribes the use of honey as sweetener.

Schauss relied upon a 12th century work called the Vitry Mazhor[8] for the information he gives us on Jewish educational practices. The date of that volume would explain why honey was used as the sweetening agent in the Jewish practice. The prophet Ezekiel mentioned that the text he was directed to eat tasted "as honey for sweetness" in the mouth. Ezekiel's book was written at a time when honey, not sugar, was the principle sweetener. So, even today when this ritual of learning the Hebrew alphabet is practiced, and it is, honey is the sweetener. Tradition is a hallmark of Jewish education.

Three of the original publications of the Machsor Vitry are extant: one in Reggio di Calabria, Italy; another in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, and the third is in the British Museum. The work was compiled in Vitry, France, by Simhah ben Samuel from manuscripts containing rules, decisions, liturgical poems (piyyutim) and customs that pertained to the Jewish faith. In addition to decisions and rules, the collection also contained remarks and critical views of contemporary authorities. The Jewish Encyclopedia informs us that two major sources upon which Samuel drew were the Seder Rab' Amram and the Halakot Gedolot.

The facsimile copy I obtained of the Vitry Mazhor had been edited by Hurwitz[9] and proves, on page 629, Schauss' reporting to be accurate. The customs described are the result of the instructions given to Ezekiel by God to go to the children of Israel, in chapters 2 and 3 of that book., and "...speak my words unto them." Ezekiel is given a "roll of a book" which is "written within and without" and is told to eat it. Ezekiel does so and finds that the book, full of lamentations and woe, "...was in my mouth as honey for sweetness."

home - links - table of contents - copyright - contact us - author

Copyright (c) 2007 - 2021 North6 Ltd.