Chapter 9: 19th Century to Present

|

Chapter 9: 19th Century to Present |

By the early 19th century, we know from a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Little Annie's Ramble, first published in a collection called Twice Told Tales[1], that sweets made with refined white sugar were available in this country and had come together with words in a way that consumers appreciated. Hawthorne puts the protagonist of his story, Annie, on her doorstep as she listens to the town crier announce a circus in town. Anxious to be away from the boredom of her street, she takes the hand of a stranger and rambles along with him for some time. They pass shops and gaze into windows. A mouthwatering paragraph is given over to the description of a confectioner's window where they see pies, cakes, heart shaped and round:

...and those little cockles, or whatever they are called, much prized by children for their sweetness, and more for the mottoes which they inclose, by love-sick maids and bachelors! (87)

Untermeyer[2] describes this cockle candy which Hershey also made in 1877 in his first venture into candy making just before he started making his famous bar. Mottoes came into prominence with "cockles," a small crisp made of sugar and flour formed in the shape of a cockle or scallop shell. Early cockle contained mottoes which were printed on flimsy colored paper and rolled up inside. The beginning of the continuing association of words and sugar in this country.

One is reminded of the fortune cookie which is brought to the table after a Chinese meal at a restaurant in this country. Shaped much like a cockle shell with your fortune inside, printed on flimsy paper, the fortune cookie may well be an ancestor of cockle candy; but, natives of the People's Republic of China report that they have never seen these fortune cookies served in an eating place at home because tariff, shipping, production and sanitation costs for them would make them prohibitive (they are made in the U.S.). By the time overhead is met, the fortune cookie would cost a Chinese citizen a week's salary.

None-the-less, paper mottoes served the purpose of bringing sugar and writing into conjunction; but flimsy paper was a short lived phenomenon. It was only 28 or 30 years until the youngest Chase invented the lozenge printing machine and words could be printed directly on the candy, another step toward taming it for its dual purposes: large candy maker's mascott and its signicant contribution to Valentine's Day (See Conversation Hearts, Ch. 11.) for those are the two, principle, employers of the sweet escagraph at present.

Mintz[3] tells us that:

...By 1880-1884, the United States was showing definite signs of developing a sweet tooth (and was) consuming thirty-eight pounds of sucrose per person per year - already well ahead of all other major world consumers except the United Kingdom.

NECCO and Hershey started to produce their trademark/name marked candy in the late 19th century and so we know that sugar consumption, reported by Mintz, was destined to rise. One company who was not so successful as the two just mentioned was Harbach Brothers of Eighth St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But in 1875 they were at the cutting edge. They ran an advertisement in The Confectioner's Journal, advertising their Centennial Confection to retailers who wanted something in stock for the upcoming 100th year celebration of 1776. I quote their ad: "a fac-simile of the Old Liberty Bell, in Harbach's original Walnut Candy. Each bell weighs one pound, is 6 1/2 inches high and 6 1/2 inches in diameter and is carefully packed in a wood box." The Centennial Confection is pictured and it's top is inscribed, as is the original, with the words from Leviticus 25:10: "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." This is a molded escagraph and did not rely on the words being printed on the candy. So to have words on candy that were molded, an idea clearly borrowed from the gingerbread hornbook molds, which the Dutch brought to escagraph creation in the Colonies, puts Harbach in league with NECCO for a moment in time. This advertisement was reprinted in William Woys Weaver's book America Eats Forms of American Folk Art[4]

Candy, after the colonial period and before the Civil War was largely a homemade luxury product, Untermeyer[2] tells us. It is amusing to note here, in passing, that chocolate began to be used as a covering for candies in 1875 and old guard confectioners thought it was a bad idea. "Dismally they shook their heads. This was too revolutionary a step"[2].

To return to the development of printed motto lozenges, and again from the work of Untermeyer:

From the moment they discovered motto lozenges in the glass candy cases, children were agog to buy them. Besides couplets, there were conundrums and tongue twisters. Grown-ups were entertained and passed them around at parties to start the ball rolling. For weddings there were wedding-day lozenges with humorously foreboding prophecies such as:

- Married in satin

- Love will not be lasting.

- Married in pink

- He will take to drink.

But there was at least one reassuring motto in the candy dish, for which everyone would search:

- Married in white

- You have chosen right.

The conundrums may sound quaintly out-dated to us, but in the sixties and seventies they were thought uproariously funny.

"What does a girl do to show her dislike of a moustache?" "She sets her face against it."

"Why is a stylish girl like a thrifty housekeeper?" "Because she makes a big bustle about a little waist."

The canal era was reflected in: "Why is love like a canal boat?" "Because it's an internal transport".

Jumping to the present, NECCO has had requests for wedding lozenges; but, since they make special motto lozenges only in 3,500 pound runs, they are unlikely to appear at many contemporary weddings. But it was possible to have escagraphs nonetheless and heart shaped as well. A betrothal announced in the Pana Palladium[5] carries the information which follows.

At a party in Nokomis, Illinois, where 12 tables of bridge were in progress, the marriage of Miss. Marion Hoyt to Sam Lewis was announced. "Brick ice cream, cut heart-shaped, was served with heart-shaped cakes, and on the latter were the words, "Marion and Sam."

Another instance of a sweet Trademark/Name escagraph which emerged in the last half of the 19th century was the Baker Chocolate Company's product. According to the public relations division of Baker's Chocolate Company, their organization holds the oldest grocery product trademark in America. It is La Belle Chocolatiere. It is the silhouette of a woman in seventeenth century costume, painted by Jean Etienne Liotard, serving a chocolate drink. It hung in a Dresden art gallery where Walter Baker, president of the company at the time, saw and purchased it in 1862. By 1872, it, along with the name Baker, served as their trademark. The Baker name appeared on their product before the silhouette of the young woman was added[6].

Large companies were not alone in their use of names printed on food as identifying trademarks. In Ohio Town, Helen Hooven Santmyer[7] tells of street peddlers who hawked their wares in Xenia, Ohio, her hometown. Playing out-of-doors, children were often the first to hear the peddlers approach and were interested, or not, depending on his wares. Of the "coal-oil man" and the "baker," she says:

We children were not much interested in him, but we watched for the baker, and when we heard his bell far off down the street we carried into the house the news of his approach. He was a round little German with a round head and drooping mustaches; he drove a high cart with a window in front from which the reins fell steeply to the horse's neck. His crackers should have made his fortune: they were thick and hard, stamped with his name in tiny letters, and eaten preferably two by two, with butter spread so lavishly between that it curled over the edge at every bite.

Unfortunately, she does not mention the baker's name. Santmyer was born in 1895 which would make this reference to street peddlers selling Trademark/Name escagraphs early 20th century. The cracker she mentioned was unsweetened. She is remembered, largely, for her novel of social behavior And Ladies of the Club.

We see that the bulk of escagraphs in the Colonies and up through the 19th century in the United States belong in the Trademark/Name category and were used as advertisements while motto lozengrs had a short life before turning into the much sleeker conversation heart.

We now return to the practices carried out for the identification of bread and note that economics had a great deal to do with the developments which took place with that foodstuff. Marketing appeared at the end of the 19th century and shows evidence of the rise of the commercial spirit. In Baking in America, Panschar[8] describes the realization of individual bakers, at the end of the century, that, in the marketplace, customers had to make the choice of which baker's bread he would buy. So, the baker needed to identify his bread, not because it was the law (assizes of bread) but because he needed to garner his share of the market.

To this end the individual baker embarked upon an entirely new experience. He had to distinguish his product from that of his competitors. Establishing a reputation for quality goods was an absolute necessity for getting repeat sales and increased market share. His first attempts represented a continuation of the earlier practice of branding his initials or trade-mark on the unwrapped loaves of bread.

That would put bakers in the vanguard of brand usage but Unilever believes pear soap makes that claim. "When shipping their items, the factories would literally brand their logo or insignia on the barrels used." But the use of the term "turn of the century" (19th) as a dating technique makes that suspect. At least, we have a good sense of the provenance of the word's meaning.

Panschar[8] goes on to say that, by the turn of the century, bakers were affixing labels to unwrapped bread which included trademarks, prices and illustrations and they also advertised in local periodicals. The baker, however, had not yet overcome mistrust; a mistrust that had existed since the 13th century and one that also existed during the colonial period here. By the end of the 19th century, one of the prominent forms of escagraph disappeared, the marked bread loaf, and the disappearing marks and initials were was replaced first by branding and finally by stickers and wrappers. Regarding the labels affixed to the bread, Panschar writes:

As late as 1910, one enterprising editor, more zealous than accurate, charged that bread labels were being "licked with saliva." While this particular canard was false, it is illustrative of the kind of press the baker of that day enjoyed.

Also motto lozenges seemed to have played their part in the sexual education of America for with the new 20th century, they began to disappear in favor of a much simpler, and more sheik version called the conversation heart. The older version was too full of intertwined roses and curlicues to be an appropriate candy to symbolize the new and sleeker form of love which the fresh century had ushered in.

As the 19th century closed, Campbells introduced alphabet pasta in their successful alphabet soup and prepared the way, for the 70 or so companies that currently make nearly 500 tons of alphabet pasta per year, for our consumption. What do you grasp by my use of the word "consumption?"; eating or general use? It is one of the few food items we encourage our children to "play" with. It would be incorrect for me to suggest that we play with and eat it in equal strides, but we do play with it. What parent has not displayed on the refrigerator door a stylized drawing of, say, a raccoon identified both as to its content and maker in alphabet pasta or some famous American Civil War edict, such as the "Emancipation Proclamation," missing a few letters but otherwise proving that we could attend to a pattern, spell and be neat. Simultaneously all accomplished with a replica of moveable type called alphabet pasta; waiting for us at the pasta counter to make soup or spell words with. We encourage children to "print" with it and adults have to restrain themselves.

Also, cake and cookie mold carving began to wane near the end of the 19th century. Those molds mentioned by Earle for making New Year's cakes and for pressing gingerbread hornbooks - probably of Dutch heritage - were loosing popularity and many baking supply companies began to reproduce the available ones in pewter and iron. Weaver tells us that:

The pewter molds were very popular with small bakeries and housewives, more so even than the old wooden ones because the cold metal made the process of stamping the dough less troublesome(117).

Nearly as difficult to trace as the sweet escagraph in the colonies was the birthday cake with "HAPPY BIRTHDAY" extruded in icing on its top or sides. In his book, the Lore of Birthdays, published in 1952, the respected social anthropologist, Ralph Linton[9], writes of the celebration of birthdays in Cleopatra's Egypt, and traces the birthday cake from Greece to the United States. He writes of the importance of greetings on birthdays.

Birthday greetings have power for good or ill because one is closer to the spirit world on this day. Good wishes bring good fortune, but the reverse is also true, so one should avoid enemies on one's birthday and be surrounded only by well-wishers. "Happy Birthday" and "Many happy returns of the day" are the traditional greetings

Linton tells us that the Greeks took over the birthday celebration from the Egyptians and possibly the Persians who were fond of sweet foods. But, in all his history of the event and the foods that accompany the birthday celebration, he does not mention a cake with any words on it. I think we can trust that, if there were any evidence of words typically being included on birthday cakes at the time Linton published his work in 1952, he would have discovered and mentioned it.

In rural, east central Illinois (my home) in 1943 there was no evidence of writing on birthday cakes although other devices were popular. I received, on my sixth birthday a cake with a music box, activated by a release bar which was tripped when the cake was cut, embedded in a hollowed out cavity in the center of the cake. It played the "Happy Birthday" song. The cake was iced and had candles, but no writing.

The Betta Products Inc. company in Oxnard, California, has been making and selling packaged individual sugar candle holders and letters which spell out "Happy Birthday" for twenty years according to their public relations division. The president of that company reports that such candy letters have been produced for about forty to forty-five years.

At the close of the 20th century, the three forms of escagraph mentioned in Section One, SWEET, LAWFUL and MOVEABLE TYPE, had disappeared or been altered significantly.

LAWFUL: Breads which carried marks or initials of

the baker were no longer required to do so by the 19th century end leaving USDA

meat markings as the only LAWFULLY powered escagraph.

MOVEABLE TYPE: These escagraphs came into popularity (alphabet pasta) at

the end of the 19th century to allow us to play with the concept of moveable

type.

SWEET: These escagraphs, directly related to the soteltie, assumed the

trademark/name bearing function and and went to work advertising. Words on

flimsy paper became associated with the candy (cockles), and gave way to words

directly printed on them after Chase invented the lozenge printer. These

new pieces of candy carried mottos (Untemeyer informs us they were called

"chicken feed") relating to love but were too elaborate to suit the preferences

of the new century and were abandoned in favor of a sleeker and totaly

un-decorated heart shapped variety known as conversation hearts. And the

birthday cake; why do we follow elaborate cutural rules and make sure our loved

ones (especially children) have a cake with one or more wishes for a "Happy

Birthday?" Perhaps it has something to do with what Linton told us about

our nearness to the spirit world and good wishes are all that we should

encounter.

Occasionally, at the end of chapters or sections, I will tack on escagraps that a person reading about escagraphs should have heard about. Newsweek[10] carried this short entry in the Periscope section:

The Chicago based Viskase Corp. has apparently decided that we Americans could be learning more from our hot dogs. The company has developed edible-ink images that transfer onto frank caseings during manufacturing. Viskase says the ink, which comes in a reddish-brown hue, could be used for a meaty message, raising the possibility that you could find "Free James Brown" under your relish. A Viskase spokesman is mum on how the technique works.

I spoke by telephone on April 20, 1993 with Dave Morris of the Marketing and Public Relations division of Viskase and asked him how that project had worked out. "There was an astounding amount of interest," he told me. But there was a production problem. The production problem turned out to be similar to the NECCO Sweetheart conversation heart problem. For specialized production runs there is a limit to the size of the run. Viskase insisted that a production run of 10,000 pounds was the minimum run for a hot dog with a message.

Viskase considered hot dogs with the "Happy Birthday" message, cartoon characters with appropriate text and company logos as possible messages for their hot dogs. In the late 80s, the American Meat Institute reported that American meat producers made and sold better than a billion and a half pounds of hot dogs yearly. If only one hundred thousandths of that amount had printing on it, it would represent a considerable body of hot dog reading. But because of production problems, and I would argue, because of the food stuff itself, the hot dog with writing never took the country's interest

The concept was resurrected in 2007 by

Mars Incorporated, makers of the popular

M&M's candy. Their

My Message product allows customers to put a personal message on the

candies at a relatively reasonable price.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, for reasons not

understood but possibly to do with marketing strategies and molding

possibilities, the United States turned to chocolate and Adrianne Marcus[11]

published The Chocolate Bible in 1979. Her book documents one after

another chocolate companies that opened during that period. Two that featured

molded chocolate, or Shaped Escagraphs, were Kron's Candies of New York City and

Confections by Sandra, Canoga Park, California. One of Kron's specialties was

Chocolate Letters and another was a ruler with the inscription The Sweetest

Rule. On the west coast Confections by Sandra went in for far more

elaborate shaped chocolates which they began marketing to

Neiman Marcus in 1978 who featured on their catalog for that year a

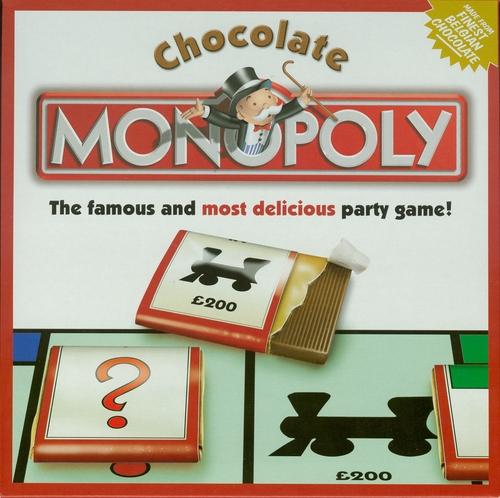

Chocolate

Monopoly game for $600.00.

Marcus tells us:

...even the tokens are perfect re-creations: everything is in chocolate, from Chance to Community Chest, to the entire chocolate board. The item is indeed both faithful to the game and to chocolate (77).

home - links - table of contents - copyright - contact us - author

Copyright (c) 2007 - 2021 North6 Ltd.